The Cloud hotspotting the planet

July 2007

I

first came across the first across the embryonic idea behind The Cloud in 2001 when I

first met its Founder, George Polk. In those days George was the 'Entrepreneur in Residence' at iGabriel, an early stage VC formed in the same year.

I

first came across the first across the embryonic idea behind The Cloud in 2001 when I

first met its Founder, George Polk. In those days George was the 'Entrepreneur in Residence' at iGabriel, an early stage VC formed in the same year.

One of his first questions was "how can I make money from a Wi-Fi hotspot business?" I certainly didn't claim that I knew at the time but sure as eggs is eggs I guess that George, his co-founder Niall Murphy and The Cloud team are world experts by now! George often talked about environmental issues but I was sorry to hear that he had stepped down from his CEO position (he's still on the Board) to work on climate change issues.

The vision and business model behind The Cloud is based on the not unreasonable idea that we all now live in a connected world where we use multiple devices to access the Internet. We all know what these are: PCs, notebooks, mobile phones, PDAs and games consoles etc. etc. Moreover, we want to transparently use any transport bearer that is to hand to access the Internet, no matter where we are or what we are doing. This could be DSL in the home, a LAN in the office, GPRS on a mobile phone or a Wi-Fi hotspot.

The Cloud focuses on the creation and enablement of public Wi-Fi so that consumers and business people are able to connect to the Internet where ever they may be located when out and about.

One of the big issues with Wi-Fi hotspots back in the early years of the decade (and it still is but less so these days), was that Wi-Fi hotspot provision industry was highly fractured with virtually every public hotspot being managed by a different provider. When these providers wanted to monetise their activities it seemed that you needed to set up a different account at each site you visited. This cast a big shadow over users and slowed down market growth considerably.

What was needed in the market place was Wi-Fi aggregators or market consolidation that would allow a roaming user to seamlessly access the Internet from lots of different hotspots without having to having multiple accounts.

Meeting this need for always on connectivity is where The Cloud is focused and their aim is to enable wide-scale availability of public Wi-Fi access through four principle methods:

-

Direct deployment of hot spots

(a) In coffee shops, airports public houses etc. in partnership with the owners of these assets.

(b) In wide area locations such as city centre in partnership with local councils. -

Wi-Fi extensions of existing public fixed IP networks .

-

Wi-Fi extension of existing private enterprise networks - "co-opting networks"

-

Roaming relationships with other Wi-Fi operators and service providers, such as with iPass in 2006.

The Cloud's vision is to stitch together all these assets and create a cohesive and ubiquitous Wi-Fi network to enable Internet access at any location using the most appropriate bearer available.

It's The Cloud's activities in 1(a) above that is getting much publicity at the moment as back in April the company announced coverage of the City of London in partnership with City of London Corporation. The map below shows the extent of the network.

Note: However, The Cloud will not have everything all to itself in London as a 'free' WiFi Thames based network has just been launched (July 2007) by Meshhopper.

On July 18th 2007 The Cloud announced coverage of Manchester city centre as per the map below:

These

network roll-outs are very ambitious and are some largest deployments of wide-area Wi-Fi technology in the world so I was intrigued as to how this was achieved and what challenges were encountered

during the roll out.

These

network roll-outs are very ambitious and are some largest deployments of wide-area Wi-Fi technology in the world so I was intrigued as to how this was achieved and what challenges were encountered

during the roll out.

Last week I talked with Niall Murphy, The Cloud's Co-Founder and Chief Strategy Officer, to catch up with what they were up to and to find out what he could tell me about the architecture of these big Wi-Fi networks.

One of my first questions in respect of the city-centre networks was about in-building coverage as even high power GSM telephony has issues with this and Wi-Fi nodes are limited to a maximum power of 100mW.

I think I already knew the answer to this, but I wanted to see what The Cloud's policy was. As I expected, Niall explained that "this is a challenge" and consideration of this need was not part of the objective of the deployments which are focused on providing coverage in "open public spaces". This has to be right in my opinion as the limitation in power would make this an unachievable objective in practice.

Interestingly, Niall talked about The Cloud's involvement in OFCOM's investigation to evaluate whether there would be any additional commercial benefit by allowing transmit powers greater tha 100mW. However, The Cloud's recommendation was not to increase power for two reasons:

-

Higher power would create a higher level of interference over a wider area which would negate the benefits of additional power.

-

Higher power would negatively impact battery life in devices.

In the end, if I remember correctly, the recommendation by OFCOM was to leave the power limits as they were.

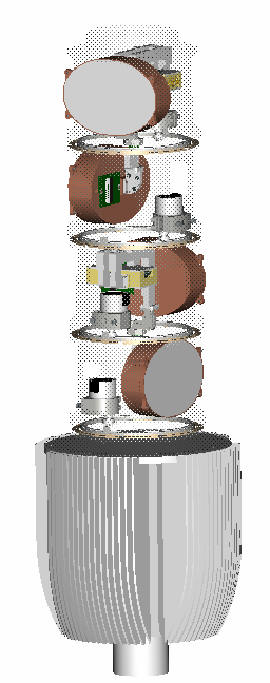

I

was interested in the architecture of the city-wide networks as I really did not know how they had gone about the challenge. I am pretty familiar with the concept of mesh networks as I tracked the

path of one of the early pioneers in the UK of this technology, Radiant Networks. Unfortunately, Radiant went to the wall -

Radiant Networks flogged - in 2004 for reasons

I assume to be concerned with the use of highly complex, proprietary and expensive nodes (as shown on the left) and the use of the 26, 28 and 40Ghz bands which would severely impact economics due

to small cell sizes.

I

was interested in the architecture of the city-wide networks as I really did not know how they had gone about the challenge. I am pretty familiar with the concept of mesh networks as I tracked the

path of one of the early pioneers in the UK of this technology, Radiant Networks. Unfortunately, Radiant went to the wall -

Radiant Networks flogged - in 2004 for reasons

I assume to be concerned with the use of highly complex, proprietary and expensive nodes (as shown on the left) and the use of the 26, 28 and 40Ghz bands which would severely impact economics due

to small cell sizes.

Fortunately, Wi-Fi is nothing like those early proprietary approaches to mesh networks and the technology has come of age due to wide-scale global deployment. More importantly, this has also led to considerably lower equipment costs. The reason that this is that Wi-Fi uses the 2.4GHz 'free band' and most countries around the world have standardised on the use of this band giving Wi-Fi equipment manufacturers access to a truly global market.

Anyway getting back to The Cloud, Niall, said that "the aims behind the City of London network was to provide ubiquitous coverage in public spaces to a level of 95% which we have achieved in practice".

The network uses 127 nodes which are located on street lights, video surveillance poles or other street furniture owned by their partner, the City of London Corporation. Are 127 nodes enough I ask? Niall's answer was an emphatic "yes" although "the 150 metre cell radius and 100mW power limitation of Wi-Fi definitely provides a significant challenge".

Interestingly, Niall observed that deploying a network in the UK was much harder than in the US due to the lower power levels of the 2.4Ghz band than in the USA. The Cloud's experience has shown that a cell density two or three times greater is required in a UK city - comparing London to Philadelphia for example. This raises a lot of interesting questions about hotspot economics!

Much time was spent on hotspot planning and this was achieved in partnership with a Canadian company called Belair Networks. One of the interesting aspects of this activity was that there was "serious head scratching" by Belair as being a Canadian company they were used to nice neat square grids of streets and not the no-straight-line topology mess of London!

Data traffic from the 127 nodes that form The Cloud's City of London network are back-hauled to seven 100Mbit/s fibre PoPs (Points of Presence) using 5.6GHz radio. Thus each node has two transceivers. The first is the Wi-Fi transceiver with a 2.4GHz antenna trained on the appropriate territory. The second is a 5.6GHz transceiver pointing to the next node where the traffic daisy chains back to the fibre PoP effectively creating a true mesh network (Incidentally, backhaul is one of the main uses of WiMax technology). I won't talk about the strengths and weaknesses of mesh radio networks here but will write post on this subject at a future date.

According to Niall, the tricky part of the build was to find appropriate sites for the nodes. You might think this was purely due to radio propagation issues but there was also the issue that the physical assets they were using didn't always turn out to be where they appeared to be on the maps! "We ended up arriving at the street lamp indicated on the map and it was not there!" This is the same as many carriers who also do not know where some of their switches are located or do not know how many customer leased lines they have in place.

Another interesting anecdote was concerned with the expectations of journalists at the launch of the network. "Because we were talking about ubiquitous coverage, many thought they could jump in a cab and watch Joost streaming video as they weaved their way around the city". Oh, it didn't work then I say to Niall expecting him to say that they were disappointed.. "No" he said, "it absolutely worked!"

Niall says the network is up and running and working according to their expectations. "there is still a lot of tuning and optimisation to do but we are comfortable with the performance."

Incidentally, The Cloud owns the network and works with the Corporation of London as the landlord.

Round up

The Cloud has seemingly really achieved a lot this year with the roll out of the city centre networks and the sign up of 6 to 7 thousand users in London alone. This was backed up by the launch of UltraWiFi, a flat rate service costing �11.99 pounds per month.

Incidentally, The Cloud do not see themselves in competition with cable companies or mobile operators concentrating as they do on providing pure Wi-Fi access to individuals on the move. Although in many ways it actually does.

They operate in the UK, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Germany and The Netherlands. They're also working with a wide array of service providers, including O2, Vodafone, Telenor, BT, iPass, Vonage, Nintendo amongst others.

The big challenge ahead, as I'm sure they would acknowledge, is how they are going to ramp up revenues and take their business into the big time. I am confident that they are well able to accept this challenge and exceed it. All I know is that public Wi-Fi access is a crucial capability in this connected world and without it the Internet world will be a much less exciting and usable place.